To-night finds me at Wagga Wagga, "the place of many crows" – hence in Latin, this is the see of the episcopus Corvopolitanus, "the Corvopolitan bishop" (in English we prefer the possessive form to the adjectival, and say the Bishop of Wagga Wagga). I had lunch at Wangaratta – as another bit of toponymic trivia, the a's in Wang. are all pronounced as a's (though some old folks there still say "Wongaratta"), whereas here the correct thing to say is "Wogga Wogga". Why is it that so many English words contain "wa" pronounced "wo" – swan, wan, want, waltz, etc.?

The ferry trip across Bass Strait was uneventful (mainly because I went to bed very early, just as we pulled out of dock in fact!), thanks be. I did have a very busy day yester-day in Melbourne, however, being up at 5.30 am (ready to drive off the ferry at 6.30) and not in bed till after midnight. Things to do, people to see...

For old times' sake I had breakfast at the European Café, just opposite Parliament House, of which eatery I was an habitué in when first studying theology... huevos madrileños, with chorizo and black pudding, went down a treat.

There's something very Melburnian – marvellous Melbourne! – about drinking good coffee, reading the newspaper, and having a cooked breakfast somewhere decent. The fellows at the adjoining table gave some local colour, by seeming, insofar as appearance, manners and overheard snatches went, rather like the stereotypical mafiosi of this city...

After thus fortifying my body, I did my duty to my soul by making a visit at St Patrick's Cathedral just a few blocks away, and caught the blessing at the end of the early Mass. Bizarrely, many older Italians were assembling outside, ladies in traditional dress, men in outlandish military outfits, since the 9.30 am Mass was to be in celebration (?!) of the anniversary of the foundation of the Italian Republic (with commemoration of the Most Holy Trinity). While I am as glad as anyone that the cursèd House of Savoy lost their ill-gotten throne, pinched from the Pope with the aid of Freemasons and worse, I wonder about celebrating a Republic...

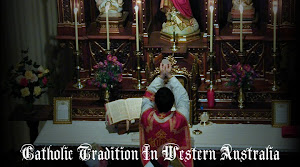

Having admired the Cathedral, I drove over to North Fitzroy, off Alexandra Parade, to attend the Divine Liturgy at the Russian Catholic Chapel of St Nicholas; friends of mine were to be singing in the choir, and the service was to be in English. (Also, because of the contretemps occasioned by my comments pursuant to my last visit to St Aloysius when the schola was singing there, as it was again on Sunday as I luckily found out in advance, I decided discretion was the better part of valour: let sleeping dogs lie.)

Archpriest Lawrence was assisted in the altar by Fr Bogdan, who I was delighted to discover is a convert priest, formerly Russian Orthodox: he and his wife have both become Catholics. The sublime mysteries of the Byzantine Liturgy lift one up into the heavenly places: I was deeply moved.

While the Hours of the Day, according to my Breviary, were of course of the Trinity, in the Byzantine Rite this Sunday is All Saints Day, since the Easterners consider that Pentecost is the manifestation of the Trinity's irruption into the world. That said, since I crossed myself the really traditional way (three fingers conjoined, two in the palm, right to left), ever so many times at the Liturgy, since one does so at each and every mention of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, I by no means missed out on remembrance of the Trinity – indeed, the Byzantine Rite leaves the West for dead in this respect. The East never ceases to praise the Trinity; how Trinitarian are Western Christians I wonder?

Fr Lawrence, as always, preached a very deep sermon about what holiness really is: the action of the Holy Spirit in one, transforming one's person. To receive the Sacrament of Christ's Flesh and Blood is very great, but this is but the beginning: thereby we ought be filled with the Spirit Who sanctifies, the Lord and Lifegiver.

After the Liturgy, I then had to find my way to the Balaclava Hotel, where the Latin Massers lunch after the Solemn High Mass. It was a good chance to catch up with friends, to profit by Fr Tattersall's counsel, and to congratulate Fr McDaniels on the occasion of his 70th birthday: ad multos annos! After lunch, I had afternoon tea with my friends Justin and his sister, Karina, at their nearby flat.

Finally, having booked in where I was staying, again for old times' sake I drove over to East Camberwell, and joined the Dominicans for Vespers there. It was great to see them again; Rev Br Paul and I caught up for dinner afterward, something I had been very keen to do since I had unavoidably missed his solemn profession and diaconal ordination last year. God willing, come December, perhaps I will be able to make his priestly ordination and first Mass...

******

After such a hectic Sunday, to-day, my longest driving day, seemed almost anticlimatic. I left at 9 am, and stopt at Euroa a bit after eleven o'clock. There's a fine little secondhand bookshop there that I came across quite providentially; I must say, the magnificent four volume Breviarium Romanum (Antwerp, 1770) on display was a bit out of my price range at $1150, but I did find some little items to console myself with.

I had lunch at Wangaratta, and was careful to visit both St Patrick's Church (which should really be the Cathedral of a Catholic diocese based at Wangaratta, if Shepparton misses out; it's silly for all north-east Victoria to be managed from Bendigo) and the Anglican Cathedral of the Holy Trinity (for the Anglicans do have their own separate diocese for this area, unusually, since nearly all Catholic dioceses in this country have a corresponding Anglican one, and vice versa). The former visit was an occasion for prayer, of course, while the latter was an occasion for snooping about and estimating the degree of their churchmanship!

I hear from my TAC sources that the new Anglican bishop of Wangaratta – once an Anglo-Catholic stronghold – is a strange and dangerous liberal: amongst recent enormities, rather than open the doors of his episcopal palace to too many visitors, he staged the elaborate dinner to host them all inside the very cathedral. For the record, their cathedral had such accoutrements as a holy water stoup, votive candle stands, statues of Our Lady, and a tabernacle with a lamp burning beside it. Unlike St Patrick's church, there were no statues of saints, but certainly stained glass images of several.

Most curiously, in a tiny oratory off to the left of the nave, on the small side altar therein were a set of altar cards (see photographs below), displaying an exact rendering into English of all the prayers on altar cards for the Traditional Latin Mass. I wonder if they are used still?

I reached Wagga Wagga in the late afternoon, and have enjoyed catching up with a friend of mine here. He tells me that there is a public Mass at 7.05 am at Vianney College chapel to-morrow, so I hope to start the day bright and early there. All kudos to Bp Brennan who established his own diocesan seminary in the dark days of the early nineties, before either the Melbourne or the Sydney seminary was reformed and purged of illiberal liberals: thanks to his not uncontroversial move, Wagga Wagga diocese has the highest priest-to-people ratio, and the youngest average age of priests, in the whole of Australia: and they're orthodox, naturally.

Happy feast of the Queenship of Our Lady to all readers!

(I must say, though, the revisers of the Roman Rite were correct in moving the feast of the Queenship to the Octave Day of the Assumption, and therefore transferring the feast of the Immaculate Heart from that day to the Saturday after the feast of the Sacred Heart. That said, why in the Novus Ordo the Visitation was moved to to-day, the 31st of May, from its old date of the 2nd of July I don't know!)